GIANT, RED BADGE OF COURAGE AND THE THING: An Interview with Robert Nichols.

Recently in response to one of my Facebook posts a woman who had played a small part in the legendary film Giant wrote me and briefly discussed the part she played in the film. This immediately brought to mind an interview I had done with actor Robert Nichols who played Pinky in the film I searched through my disks and luckily I had saved it and decided to post. It is probably the most conventional interview I ever did.

In our talk Nichols not only discusses Giant but also The Thing From Another Planet and director Howard Hawks, The Red Badge of Courage and director John Huston as well as working with Marilyn Monroe. It should be remembered that The Red Badge OF Courage had been heavily mutilated after two disastrous previews and many—including Nichols—who has seen the original version believe that, in the process, a film masterpiece was destroyed.

Nichol’s is one of those actors who people have a hard time remembering his name but the moment they see his face know immediately who he is. I found his observations refreshingly insightful and hopefully you will too.

EGAN—Even though Christian Nyby is listed as the director of The Thing, I can’t believe anyone else but Hawks directed it.

NICHOLS—Well, you’re right. Hawks directed every frame of it. Chris was with him all during it but it was Hawks who directed.

EGAN—You think he was doing that as a favor to Nyby who was his cutter and wanted to direct?

NICHOLS—Of course he was. Chris was a marvelous cutter and a good director but he’s not…He’s good, he’s competent, he knows the job. There’s nothing wrong with his work but it’s not brilliant. He never direcedt anything close to The Thing.

EGAN—If The Thing was the only Hawks film I ever saw, I wouldn’t have to think twice about calling him a genius.

NICHOLS—I agree. I think the man is a genius. It’s funny, I don’t know how he directs, really. Which again is the key to a really great director. In I was a Make War Bride, I was a fresh kid out of drama school and I didn’t think he liked me. He never smiles. He was always kind of military. He terrified me. In one scene I had a reaction shot. It was my first time in front of a camera and Hawks said, “Bob, do you realize that right now your eyebrows are going up 15 feet at Radio City Music Hall.” That was the direction he gave me on Male War Bride. Then, at the end of the picture he said, “You come to Hollywood and I’ll put you in my next picture.” Which was The thing.”

THE THING FROM ANOTHER PLANET. ROBERT NICHOLS IS ON FAR LEFT.

EGAN—How was it working with Hawks?

NICHOLS—A unique experience. Everything was improvised. It’s not improvised on the spot; at that moment. The way Hawks works, at least the way he worked in Male War Bride, The Thing and The Big Sky, is that he threw out the script. You don’t learn the lines or pay any attention to it. You arrive on the set in the morning and Hawks has his secretary right there. And he would say, “Now this is the scene we’re going to do, where you remember in the script it says such and such.” We’d sit around and he’d say, “Now, Dewy, you say this. Ken, you say this; Jim, you say this and Maggie, you say this line. OK, let’s hear it.”

He’d give you a semblance of the line you are supposed to say and you’d say it pretty much as Hawks said it, but in your own words. He would listen and then he’d say, “OK, now after Jim says so and so, you say such and such.” So you would be building up the scene. Then you would get on the set and you’d bock it. Every single one of us had stand-ins – even the bits. Then while it was being lit for the next couple of hours with the stand-ins, we’d rehearse the scene even more. Improvise it, play around with it, and work up nuances.

By now it’s noon and after lunch he’d shoot the master shot. So you’ve been there four hours. Then, frequently, he’d take someone aside who hasn’t said a word and he’d say in that quiet voice of his – he never raised his voice – “OK, after Jim says this line. I want you to throw in Bla Bla Bla. Got it? OK, real fast now, I want you to get it in then.” So the scene is being played the way it was supposed to be played. You’d been doing it for a couple of hours and you’re reasonably sure about the dialogue. It’s been a little tentative but its reasonable. Then, suddenly, out of left field came a line you never heard before from somebody who hadn’t been saying anything. Everyone would react to that, and that was the take Hawks was going for, and that’s the one he’d print.

EGAN—That’s why it was all so natural.

NICHOLS—DO you remember the sequence where the hand begins to pulse and come to life? Well, we had this dumb piece of plastic – the plastic hand. We all clowned around with it and played with it in the morning while we were getting set up and were rehearsing. Then we went to lunch and came back. We all got around the table, looked at the dumb plastic hand – which was there like it was before – and started running the dialogue while the cameras were rolling. Then, suddenly, the damn thing began to move and pulsate and all of us were going, “Jesus, what the hell is that!!” During lunch they had sawed a hole in the table and used another arm which a midget under the table moved on cue. Well, I nearly died.

EGAN—I saw that on screen.

DIRECTOR HOWARD HAWKS WITH HIS WIFE SLIM

NICHOLS—You see, we never knew where we were going. The only person who knew what was happening was Hawks. He undoubtedly saw the film from the opening titles right through to the end. But he never let us know, which kept us hopping. We didn’t know who was going to be killed or who wasn’t. Also, the overlapping dialogue all the way through; he absolutely insisted on it. He wanted the audience one step behind. He’d say, “We can not allow the audience to get ahead of us. We’ve got to make that audience work and be saying, “What are they saying, what’s happening?” Because the audience has one chance to get ahead, they’ll say, ‘this is fakey,’ and we’ll lose them.’ ”

EGAN—How was it to first work with a director like Howard Hawks?

NICHOLS—Hawks was already a legend in the business when I first went to work for him. I had been raised on Howard Hawks’ pictures. So, Hawks was man I admired tremendously. I never felt that I could get close to him. He terrified me because he was so sure of himself. He was such an incredible person. In the beginning I would never dare ask Hawks anything.

EGAN—And On The Thing?

NICHOLS—One day I had been playing a scene and I felt uncomfortable about it. I wanted Hawks to tell me it was good, so I asked him if was all right. And he said, “Bob, if it wasn’t the best it could be, I wouldn’t print it.” And he wouldn’t because he’d go up to 24 takes sometimes.

NICHOLS—Well of course. You see Hawks is basically a very shy man and this is something that I didn’t understand at the time. I think I would understand it now, but I didn’t realize it at the time. He gets to know you. Hawks likes to use people that he knows. He sees them over and over again. If you become a Hawks actor, you’re going to work a lot like I did. He gets to know his actors and then uses them as they are. In The Thing I was on it 19 weeks and I only got one piece of direction. He took me aside one day and he said, “Bob, you’re not on the stage, now.” I knew exactly what he meant and I changed my performance. I pulled it down and started being real again.

EGAN—He did it with the technical people also?

NICHOLS—Hawks always worked with a marvelous cameraman, Russ Harlan, who was a buddy of his.

EGAN—Do you think that rapport is really necessary on a film?

NICHOLS—In a Hawks film it sure makes everybody work. Bill Kniff the gaffer was on every Hawks’ film and Hawks always worked with Russ. He used Chris Nyby for editing. Lori Shirward was always his production secretary. In this way, the crew knew exactly what Hawks wanted. It was a way of working that was so easy. There was never any cussing. There was never any loudness or any frantic things. Never any rush. Hawks’ entire way of working was quiet, relaxed and easy. There was never any need for Hawks to assert himself because he is. I admire him more than anybody I have ever worked for. He’s such a gentleman. He dresses with such wonderful assurance and style. He’s not dressing because this is the way you dress this year. He dresses this way because this is what Howard Hawks wears. He’s flown his own airplanes and he’s a man of great…he’s wonderfully red in everything about him. He’s a total man. With so many directors, even some very good ones, they are so locked into just films that they are not total men. Whereas Hawks really is.

EGAN—Well the thing I really admire about Hawks is that he was such a great artist that he didn’t have to tell people that he was. Then he was sort of discovered at a time when most people thought that he was a hack.

NICHOLS—Well, you see, he’s not only a great artist, but he is also such a strong individual that it really didn’t make any difference to him. You see, he knows how to live. For example, when we were making Male War Bride in Mannheim, Germany and suddenly a large fog descended upon us in the middle of a shoot. So Hawks said, “I’m going hunting in Switzerland, call me when the fog lifts.” So, here he is directing this enormous production with Cary Grant, Ann Sheridan and all those people and he goes off with Charlie Lederer, the writer, to Switzerland for three or four days. Then the fog lifted and he come back. How’s that for class.

EGAN—Other directors would have been pulling out their hair.

NICHOLS—It was Howard Hawks, and he knew what he was doing. And the studio knew that they were going to get a film from him so why sweat.

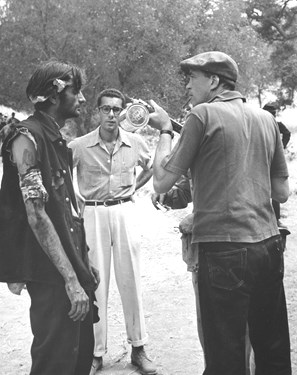

DIRECTOR SAM PENINPAH

EGAN—I think his influence on other directors is profound. A director who’s work in ways resembles Hawks’ is Peckinpah.

NICHOLS—Well, now you’ve hit a nerve.

EGAN—You don’t like Peckinpah?

NICHOLS—I don’t like him personally, and I’ve known Sam since college. And of course, I will never work for him.

EGAN—You don’t like his work?

NICHOLS—To begin with, I don’t believe his stuff. I think he has such a perverted sense of life. I just don’t believe Sam at all. I think that everything he does is exaggeration.

EGAN—Not any of his films?

NICHOLS—I think Sam has made good films. I think Sam has made some damn good films. I think his film, Ride The High Country is wonderful.

EGAN—If you look at the Wild Bunch, or any of his other films, they’re variations of the same themes.

NICHOLS—I think he has perverted it. I think he’s reached a point…I just think that Sam has such a distorted point of view and I don’t believe that Sam sees this. Obviously, the way I feel about him has got to influence the way I feel about his films.

EGAN—I’ve heard that he’s not the most pleasant person to be around.

NICHOLS—Sam’s a son-of-a-bitch. Look, when I first knew Sam he was directing community Theatre in Long Beach. I was an established actor and he asked me to come and see a production of The Glass Menagerie that he was directing. It was terrible. It was awful. It was painfully bad, and Sam’s contribution was part of the problem. I didn’t say anything. I didn’t say it was terrible because I don’t do that unless they ask me. But unfortunately, Sam asked and I said, “Sam, it’s terrible.” And then he asked me why, and I told him. Consequently Sam has never been too fond of me. But he shouldn’t have asked me if he didn’t want to know. And that is Sam.

I think that Sam’s whole attitude toward life and toward art is so distorted. And I think it’s Sam’s distortion. I will not deny the man’s talent. He’s extremely gifted. But I don’t know how much longer he’s going to be able to function as a person. Jesus, he’s drunk all the time now. I’m sorry about it. I have so many friends that were friends of Sam. None of the old friends are anymore. I know his sister. I think that there’s a bitterness and an anger in Sam that has been very destructive to the man.

EGAN—But his films are extension of that perspective.

NICHOILS-I don’t deny their strengths and but I hate what he says. Not that everything has to be sweetness and light. But I thing that Sam is really perverted.

EGAN—In many ways Hawks and Peckinpah films are concerned with many of the same issues. The difference is that Peckinpah presents the worst aspects while Hawks the best. But then again, Hawks succeeded in the Hollywood system. He had a lot of power and was in control. Peckinpah’s films have been mutilated one after another. He’s not in control and so, his cynicism is his reality

NICHOLS—I think that Sam could have been in control of his life. I think if Sam had more personal discipline. I think he could have. I think Sam lets things get out of hand. I know an awful lot of things about Sam, and have for a long time. I think…well…never mind.

EGAN—You think discipline is the key, then.

NICHOLS—What I feel about art is that it must convey a total sense of life and life is not made up of anger and violence. It’s also not made up of just beauty and love. They all come together and when it can express the entire range that, to me, is when something becomes art. To try and make an audience believe the world is all rotten or it is all beautiful is just plain foolish.

EGAN—All right, moving on, you also worked with John Huston on The Red Badge Of Courage and George Stevens on Giant. On the set, what was the difference between these two directors.

NICHOLS— Stevens was very quiet and very kind of…well he was a director, very much a director, but never the dominating figure. If you were on a Steven’s set you’d have to ask which one was the director. Whereas with Huston, there was no question that he was the star performer.

HUSTON WITH HIS WIFE RICKI SOMA ON LOCATION

EGAN—A lot of varying things have been written about Huston but how did you feel about him during Red Badge.

NICHOLS—I had a warm relationship with Huston. I lived next door to the assistant director on the picture, Reggie Callow. Reggie introduced me to Huston and, in the meantime, I had just been cast on the stage in She Stoops To Conquer. Huston’s wife, Ricki Soma, was in the play and Huston came to the opening night and he said, “Yea, you’re in my picture. But you’re not doing a bit. I want you to be the pig soldier.” He was very warm to me, but he could be a son-of-a-bitch. He can be very sadistic and hard. But in my relationship with Huston, which granted was very brief, he liked what I was doing on the stage and I had just gotten married and he and his wife were very warm to us.

You judge people on how they are towards you. I am such an enthusiast. I was thrilled to be working in films and I think Huston got a kick out of me and so what I saw wasn’t what a lot of others saw.

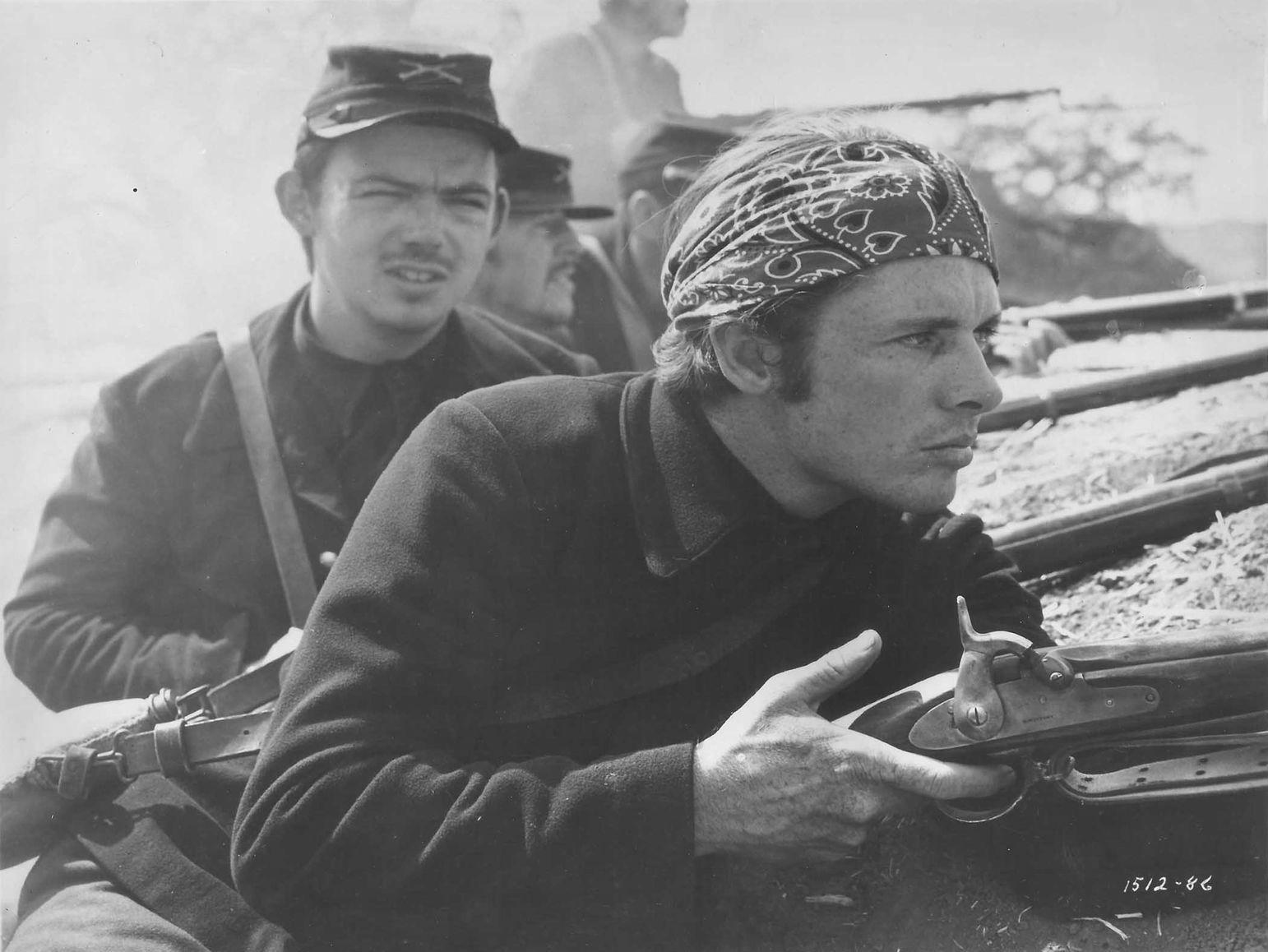

EGAN—What do you think Huston was after in Red Badge?

NICHOLS—What he did was to put that book on the screen. It was visually magnificent. Well that’s the wrong word. It was visually real all the way through. You really felt like you were in a Brady photograph. I think if they had not done the editing job on it that they did, that it would have become, ten-twenty years later, a classic. The thing that was extraordinary about it, and you can still sense this in the cut version, is that it was like stepping into a Brady photograph. I really believed I was back there. Most of us who were in the picture were veterans and the battles were very believable. It was like being in the army, except here we were in Blue Uniforms and carrying out of date riffles. It was a very real experience and that’s what was so interesting about it.

EGAN—Did you do to any of the previews?

NICHOLS—I went to the preview when it was shown in Westwood on Peco. I saw the uncut version.

NICHOLS—How did the audience react. Were they hostile?

NICHOLS—I remember it very well. It was the first time that I saw myself on the screen. There wasn’t hostility; there was boredom which is even worse. All the people that were in the film knew it was being sneaked, so I went to see it with a whole bunch of actors with their wives and friends. We were all sitting together and we were just knocked out by it. I was magnificent. But as far as I can tell, from the reaction of the audience, they certainly were not hostile. It was more like, “OK, that’s all right, now let’s get on with the other feature which we came to see.”

EGAN—Was it badly destroyed in the re-cutting?

HUSTON DIRECTING ROYAL DANO AS THE TATTERED SOLDIER

NICHOLS—Yes. What they did. They chopped out the best scene in the picture; the death of the tattered soldier. I had never seen a better job of acting in my life. Royal Dan was magnificent. Royal Dano can play anything. He was superb in that film.

EGAN—How would you compare what’s left of his part with the whole sequence?

NICHOLS—You only see the beginning. You didn’t see where he was going with it. All you saw was the establishing shots and didn’t see what was extraordinary about it. Here is this guy talking to the youth about going back to Ohio and what it’s going to be like when he gets home. He’s saying that he can’t die because he’s got a wife and kids. You don’t realize it but you are watching this man die. He’s talking about living and then all of a sudden he collapses dead. It was stupendous. The best thing I ever saw.

EGAN—From what I’ve read, I get the sense that Huston conned performances from his actors.

DIRECTOR HIUSTON DIRECTING AUDIE MURPHY AS WELL AS PLAYING A BIT PART IN THE MOVIE

NICHOLS—He worked very hard and very specifically with Audie Murphy and Bill Malden. He spent a tremendous amount of time with them. You see, in the film, outside of Audie, Bill Malden and Dierks, nobody else had a really big part. Royal Dano had that one incredible scene, which is one of the greatest scenes ever, but it’s not there anymore.

EGAN—It seems so sad about that film. A lost masterpiece.

NICHOLS—As I told you, I saw the original version before they added the narration and before they destroyed it and I don’ know. What I’ve always found very hard to figure out is why Huston, as powerful as he was at the time allowed them to do what they did to his picture. I don’t know. I really don’t know. It’s a very sad thing.

EGAN-I’ve heard that MGM is considering restoring it to the original version. The only trouble is that they can’t find the missing footage/

NICHOLS—I think that it would be devastating. I think now, in particular, 25 years later, people would say, “What an extraordinary film. Why didn’t we recognize it?”

BILL MAULDEN AND AUDIE MURPHY

EGAN—We’re you close to the decision making on it?

NICHOLS—When you’re on a film, the director, the producer and all those people are over there. It’s hot, we’re under the trees, working when we’re working; chasing around through those damn battles with all the explosions going off around us. When they’re not shooting, we’re laying around talking to our buddies about the next job. You see, I just wasn’t involved with anything higher up.

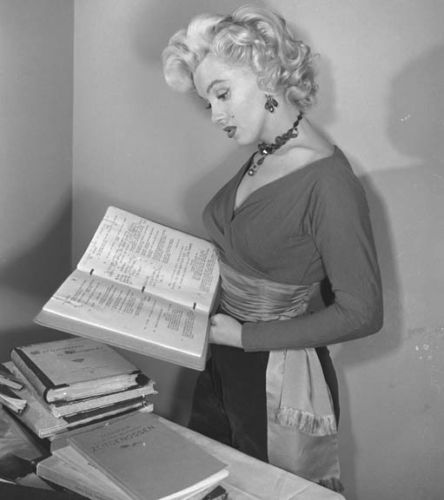

MARILYN MONROE

EGAN—You worked with Marilyn Monroe, didn’t you?

NICHOLS—I worked with her twice, in Gentleman Prefer Blondes and Monkey Business. I didn’t know Monroe, I just played scenes with her. Beyond a doubt, she as the most delectable woman that I ever, ever encountered and I’m not that turned on by actresses. I find them mechanical.

EGAN—Did the screen reduce the impact?

NICHOLS—I think film did something more. I think it picked up Monroe and made her more than she seemed in person. It does that sometimes. She was just gorgeous, just gorgeous. That extreme sensuality with that little girl thing made for a very potent combination.

EGAN—I’ve heard when she walked down the lot, all eyes were on her.

NICHOLS—On the first day of shooting Gentleman Prefer Blondes Jane Russell came on the set and Jane looked great. Everybody loved Jane. Fine, ballsy dame. Fun to work with and a good pro. Not a great actress; more a personality, but who cares, she was fun to be with. Anyway, Jane was the first to get there and then about a half hour later Marilyn quietly oozed onto the set. Every eye went BONG. My god! You couldn’t help it. Jane Russell might as well have been one of the fellas, because here was the most gorgeous thing my eyes had ever seen. And this was a set. I guess there were 150 of us there. But when Monroe made her appearance, she was it. You knew there was something there.

EGAN—Tell me about Giant.

NICHOLS—I think Giant was the most exciting film that I have ever been in. Before I finish my career I would like to have one more Giant.

EGAN—Why?

NICHOLS—Well, working for Stevens was very exciting. To begin with Giant was the one picture I went into where, when I got the script I knew I was in for something exciting. They were talking about the picture for a year before it went into production. Before Steven’s went into production he worked on it for two or three years. There is a aura about working with Stevens. I was flabbergasted when I got the part of Pinky. I couldn’t believe it.

DIRECTOR GEORGE STEVANS WITH GIANT WRITER EDNA FERBA

EGAN—How was Steven’s as a director?

NICHOLS—This is one of the things where Steven’s was so interesting. He would deal with every single actor in a different way. Huston dealt pretty much the same with every actor that he was directing. But Stevens would direct every actor differently.

Jimmy Dean tended to get stale if he repeated too much. The thing that Jimmy had, which was so extraordinary, was absolute freedom. He was totally spontaneous. Anything could happen with him and you never knew what the hell he was going to do. He would change things and change lines and everything else. He kept you jumping all the time. So, Steven’s would constantly give him new things to do and was constantly making it fresh and changing it for Jimmy.

STEVENS DIRECTING JAMES DEAN IN GIANT

Now with Rock Hudson, who was at that time a very limited actor and rather passive, Stevens would get him all charged up in a scene. He’d pound emotion into him and get him all churned up and hot to act. Then he’d say, “Don’t do so much, pull it down, pull it down.” And Rock would pull it down so you got the feeling of a man ready to explode. That’s what Steven’s was going for and that’s what he’d print. So, for the first time you saw Rock Hudson as this real passionate guy.

EGAN—Is it true Steven’s shot everything from every angle?

NICHOLS—Steven’s would shoot and shoot and shoot.

EGAN—Do you think he shot like that because he didn’t have a conception of the film and hoped to make it in the cutting room?

NICHOLS—No. I don’t think that’s it. I think that Stevens loved to cut; really loved to cut and liked to have everything to use. Also, he went to an earlier day when they used to do that. In the 1930s and 40s films had long, long schedules and a they had lot more money. You can’t afford to do that anymore. It takes a tremendous amount of time.

ARMNDO—Giant came in for around $6,000,000.

NICHOLS—And that was an awful lot of money at that time, a tremendous amount of money for a film. We shot on it for 26 weeks.

EGAN—Today the average shoot is six to eight weeks. How were you paid; a flat fee or weekly.

ALEXANDER SCORBY, ELIZABETH TAYLOR AND SAL MINEO IN SCENE FROM GIANT

NICHOLS—I was on a weekly and because it went way over schedule I made a lot of money on that film. Alex Scorby for instance who played Old Polo, Alex had two lines in the film and he must have been on the film for at least 10 weeks and probably more like fifteen. He was getting an enormous salary and made a fortune. Sal Mineo had only one day’s work on it, but because he was under contract to Warner Brothers he didn’t get more than his weekly studio check.

EGAN—Yet he was eighth or ninth in the billing.

ROBERT NICHOLS AS PINKY IN GIANT

NICHOLS—And the detail in a Stevens production was incredible. They wanted me to have red hair. So, they dyed my hair for two solid weeks and tested it until they got the color that they wanted. I thought I was going to die. And another little detail. At the end of the film, for the big banquet, they made me a pair of boots with silver filigree. Honest to God they were real silver filigree boots that must have cost 200 bucks. Well, they were never seen in the film, but I had them on and don’t you think that I felt like a millionaire wearing those $200 boots with silver filigree.

EGAN-One of the things that I find remarkable about the film is the feel it has of Texas. I’ve been there, and a lot of it had to do with the performances.

NICHOLS—We spent an awful lot of time in Texas and lot of time with Texans and while we were down there we literally became Texans.

EGAN—Do you think he shot it down there for that?

NICHOLS—Of course he did. Because we were on it…I was hired a good month before he started. We all went down to Texas and shot in sequence in Marfa for several months. They even shipped down that famous set – the big house – that everyone remembers from the film. They built two of them in Hollywood and shipped one down to Texas. It was only the façade – a front with the porch and two sides and part of the roof. They used this for all the exterior shots.

We started at the beginning shot right to the end for all the exterior shots. Then we went back to Hollywood and we shot in sequence on the interior shots on the second house which was built on a Hollywood sound stage.

EGAN—How did you feel when you finally saw the film?

NICHOLS—The first rough cut of Giant ran over five hours. Jane Withers and I had wonderful parts. When I went to see the final cut I just sat there and cried. So much was gone; so much really good stuff. It was very frustrating. A lot of Mercedes McCambridge was gone too.

EGAN—Was it a shock?

NICHOLS—I’ll tell you, we did a scene in the library when they’re reading the will and they bring Jet Rink in to tell him he’s got the land and then try to buy him out. In that library there was Rock, Jimmy Dean, Charlie Watts, Monty Hale, Shep Willy and me. In the scene I was over in the corner sleeping. During the entire scene I just opened up one eye at one brief moment to listen to something and then I went back to sleep again. Stevens shot the whole scene with a close-up of me just sitting there sleeping through the whole sequence. Obviously he was not going to use anything but one flash of it. I knew that when I was doing it. So, even though it’s been shot, and even though they use it in the rough cut, I know damn well when they start trimming, it’s got to go. I wasn’t necessary and they need to stick with the story. In that scene, they used one brief little flash; probably no more then 1 ½ seconds of me. But that’s what I expected.

EGAN—In a way I would think that’s kind of defeating.

NICHOLS—Let’s face it, you’re making a film that’s going to be about three hours long, and it’s a film about Liz Taylor, Rock Hudson and Jimmy Dean. If you’re a supporting actor, whatever you can contribute, that’s it. You cannot, and should not, expect anything more. When you’re in a scene with a big star, I don’ care how good you are, the focus is going to be on the star because that’s who the people are interested in seeing. That’s where the strong angles are. That’s where the action usually is. A supporting actor who can make a real impact in that kind of situation is either very lucky or goddamned brilliant. The opportunities to do that, when you are a supporting actor are few and far between.

Robert Nichols Died in 2012 at age 88.