ACTOR ANTHONY HOPKINS: AN INTERVIEW

ANTHONY HOPKINS IN 1975

At the time of this interview Anthony Hopkins was on tour promoting a TV movie about the Lindberg kidnapping. He portrayed Bruno Hauptmann, the convicted kidnapper; a performance that would earn the actor an Emmy. This interview–one of my first–was conducted 15 years before Hannibal Lector mesmerized film audiences, won Hopkins an Oscar and made him a household name. At the time Hopkins was an established stage actor who stared in films and TV but hadn’t as yet reached superstardom.

EGAN—Did you believe that Hauptmann kidnapped and killed the Lindbergh baby??

HOPKINS— There’s a question mark left at the end and I think it’s right that a question mark is left. Historically there’s a question mark and because of this he shouldn’t have gone to the electric chair. They never proved conclusively that he did it.

EGAN—Is that what he was hoping for?

HOPKINS—I don’t think so. His defense attorney pleaded with him to confess. He said, “If you tell the truth now the Hearst papers will give your family a fortune and you won’t go to the chair.”

EGAN—Why didn’t he, then?

HOPKINS—that’s the big question. Did he, or didn’t he. When I was doing Hauptmann I had to believe that he did it. I was Hauptmann. I kidnapped the child and killed it in a panic by accident. I had to do this in order to build it as background. But they never should have sent the guy to the chair. To send Hauptmann to the chair was a diabolical piece of miss- justice. He should have been put in a mental hospital.

EGAN—He was crazy?

HOPKINS—Yes, I think he was NUTS! He was also a very stupid man.

EGAN—how do you go about playing a stupid man?

HOPKINS, LESLIE CARON AND ANTHONY EDWARDS IN QBVII

HOPKINS—He can be played in many ways. I thought Dr. Kelno in QBVII was stupid. Hauptmann was stupid because of his arrogance and his lack of sensitivity. We can all be stupid in that way.

EGAN—I thought with Kelno you gave a fully realized performance. How were you able to do that in the short time that TV production gives you?

HOPKINS—I like working under pressure. I think I had two weeks at most to prepare. What I did was go around to as many people as I could. I found two Jewish friends who had been tin Auschwitz. Valdek Sheybal, who played Sobutnik in the film, had been in an SS labor camp. Then I went to the other end of the pendulum and found a Polish fascist who was anti-Semitic. He said, “Have you ever met an anti-Semite before?” I said, “No,” and he said, “Well, you’re looking at one now.” I went to him to get the Polish accent, but he fed me enough to help me build the character.

EGAN—did you improvise?

HOPKINS—I love improvising. This is the reason why I love working in America. The American actor works much harder internally than the English actor. He works through an internal monologue. The English actor works externally; on good speech and good technique. It’s like covering two book covers very well but not having very much inside.

EGAN—How did you become interesting in the American school of acting?

HOPKINS—I was lucky. When I was at the Royal Academy 15 years ago, I met an American student who introduced me the whole system of method acting. I’m a method actor. I like going inside the character and then letting it come out. If you look at actors—and Lee Strasberg would kick my ass if he heard this—but I think by watching actors one learns a great deal. I’ve watched people like Brando, Spencer Tracy, Montgomery Clift and thought, “How the hell did they arrive at that.” So in my own way, during the last 15 years I’ve been working very steadily to achieve my own identity as an actor. I did, I confess imitate a lot of actors in the beginning but then, because I work internally, I found my own. When someone asked Spencer Tracy, a supreme craftsman who had something internal, “what is the secret of acting”, he said, “Just listen.” Laurette Taylor, who along with Bette Davis is probably is one of the world’s greatest actresses, was asked by Robert Lewis of the Group Theatre, “How the hell do you work. You never came to the Actor’s Studio?” She said, “I just listen.”

EGAN—I saw Bette Davis on the stage in NIGHT OF THE IGUANA. She was even more electric, if that’s possible, than in her films.

BETTE DAVIS IN WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE

HOPKINS—She’s got daring. When I saw BABY JANE, I thought, “How the hell does she get away with a performance like that. It’s outrageous.” Yet she gets away with it because she’s got guts. Brando’s also an outrageous actor with a lot of daring.

EGAN—I think his work with Kazan is some of the best screen acting ever.

HOPKINS—I think Kazan is probably the greatest director.

EGAN—He’s such a performer oriented director that when he gets together with a great actor, there’s a magic.

HOPKINS—Kazan likes to improvise a lot. You look at the things that he did with Brando and James Dean.”

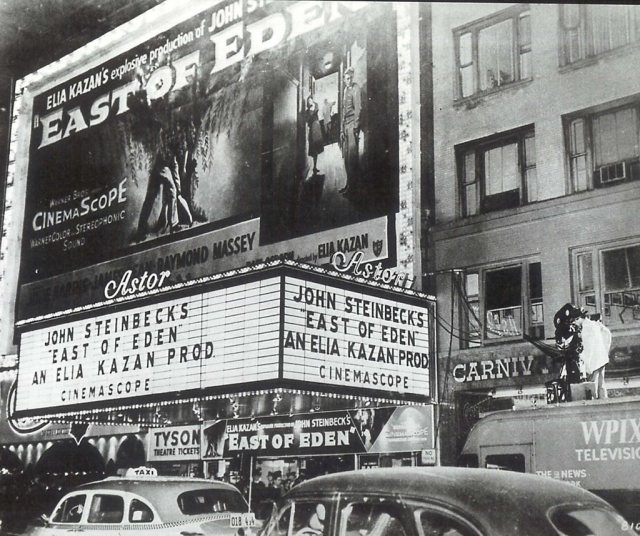

EGAN—In EAST OF EDEN he made James Dean.

HOPKINS—In that film he did marvelous things with Dean. One day Dean was playing the scene where the Raymond Massey character made him read the Bible.

EGAN—“Don’t read the numbers, Cal.”

EAST OF EDEN’S 1955 PREMIERE AT NEW YORK’S ASTOR THEATER

HOPKINS—Right. Kazan went up to Dean and said, “Say something really filthy to Massey.” Massey was an excellent and very fine actor but a very uptight man. The camera was running and when they said, “Ok action.” Dean came out with all these obscenities and Massey stood up outraged. That was the shot Kazan wanted and he said, “OK, cut.” He did the same thing to Brando.

EGAN—What did Kazan tell you about Dean?

HOPKINS—He said that after a while he found James Dean a real pain in the ass to work with. Dean was starting to get spoiled, but his potential was just extraordinary. There’s a marvelous story Kazan told me. They sneaked EAST OF EDEN up in in some tiny cinema. They invited all the local townspeople; especially the kids. Kazan said that as soon as the projector switched on and James Dean was sitting on that sidewalk suddenly all those kids started screaming. Kazan thought, “My God, Why?” It’s this quality that Dean had which we’ve never been seen since.

EGAN—I think you also have a quality. Did directors help you develop that?

HOPKINS—I’m lucky because I’ve worked with three appalling directors, who shouldn’t be called directors.

EGAN—For example?

HOPKINS—Tony Richardson.

EGAN—You’re joking. Did you see THE LOVED ONE or CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE?

HOPKINS—Yes, but he’s an appalling director! I worked him with on HAMLET with Nichol Williamson.

EGAN—Wait a minute. He’s a very good director.

HOPKINS—He’s a lucky man, because he has his cameraman and….

EGAN—What about TOM JONES?

HOPKINS—Interview Albert Finney about TOM JONES. Albert wanted his name taken off the film.

EGAN—What are you talking about? TOM JONES is a remarkable film.

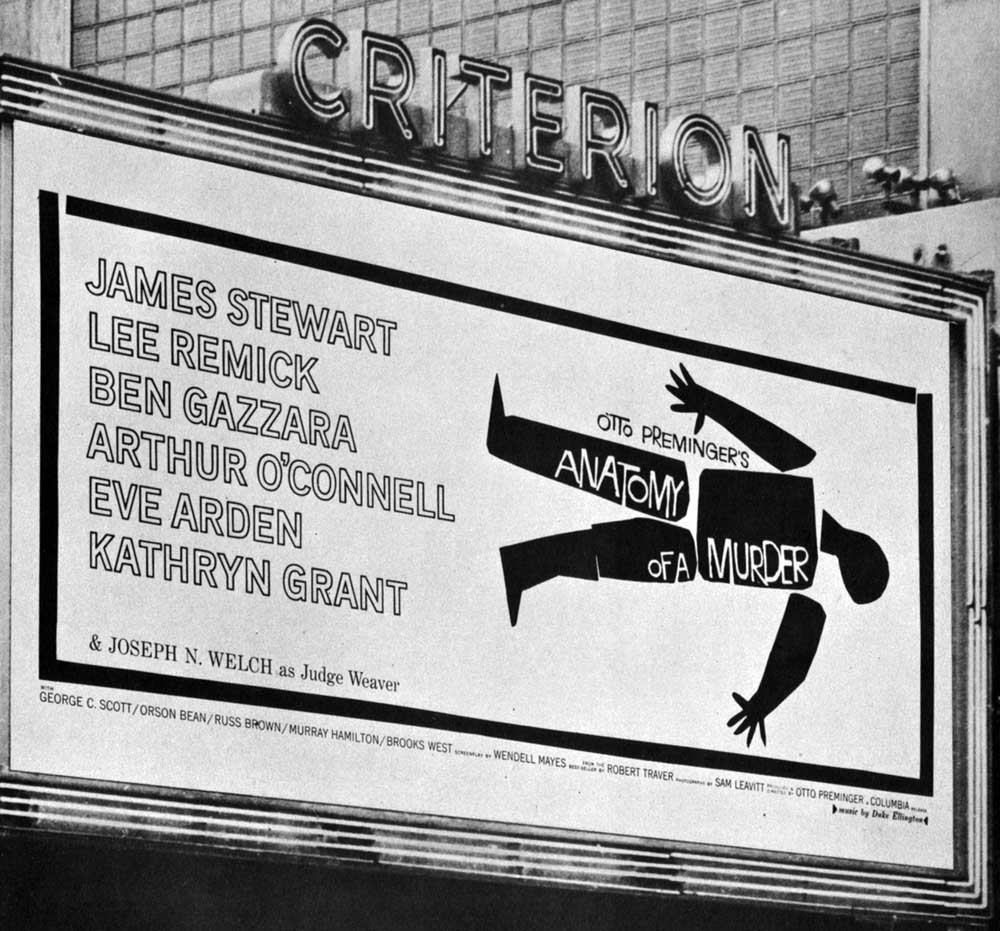

HOPKINS—Richardson is a phony. He’s a fake. He’s like Otto Preminger. Preminger is a fake.

EGAN—That’s just not true. Preminger is one of my favorite directors. He’s a brilliant director. Look at ANATOMY OF A MURDER. It’s a masterpiece.

ANTONY OF A MURDER PLAYING AT NEW YORK:S CRITERION THEATER IN 1959

HOPKINS—Yes, that’s a superb film.

EGAN—There’s such a layered richness in all his films. Even in his worst movies there’s always something interesting.

HOPKINS—That’s maybe so, but anyone who comes on the set and screams and shouts.

EGAN—You’re talking about how he treats actors.

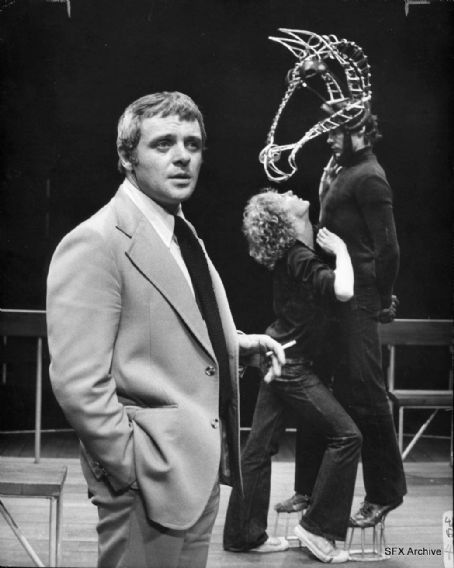

HOPKINS—One moment. When Kazan came to New York and saw EQUIS in which I was staring. He asked me about the director, John Dextor and I said, “He’s a brilliant director but he shouts and screams and terrifies us.” Kazan said, “Therefore, he’s not a brilliant director. Anyone who screams and shouts is sick.” You find with directors who are monsters that they’re lucky when their work is good.

HOPKINS AND PETER FIRTH ON BROADWAY IN EQUIS

EGAN—I believe, where the director is concerned, an actor is like a child. In rehearsal or shooting the director is the only audience that the actor has and so he is very dependent on him.

HOPKINS—That’s exactly why a director is very important. If you constantly, over the years, say to a child, “Here’s a candy, but you can’t take the wrapper off,” or you lock a child in a closet for most of its growing years, you create tremendous problems in that child so that when it grows up, it’s a destroyed human being. You do that to an actor and you will frighten the actor out of a performance.

EGAN—Actors have a sensitivity and it’s a very delicate part of them.

HOPKINS—It’s almost infantile.

EGAN—Right. Something exquisite. If you step on that and you hurt that it’s like putting a knife into the performer and that’s the worst thing that you can do. But have you ever thought that Preminger might deliberately be doing what he does in order to get exactly the performance that he wants. He’s gotten some marvelous performances from his actors.

HOPKINS—Well, you see Preminger actually killed an actress who was an alcoholic. She was in BUNNY LAKE IS MISSING, with Laurence Olivier. It was Martita Hunt. She played the old woman living in the attic. She was an alcoholic and three months after that film was completed she died of alcoholic poisoning because she had nothing else to do but drink herself to death.

MARTITA HUNT AND CAROL LYNLEY IN BUNNY LAKE IS MISSING

EGAN—But she was marvelous in the film, just marvelous.

HOPKINS—He called her an old bag and an old whore and a has-been. It simply destroyed her. He also gave Keir Dullea a terrible time. Preminger was a bully. It was Olivier who finally went to him and said, “If you don’t stop this, this instant, Noel Coward and I are walking straight off the film. You are a manic!”

I don’t like maligning people, but I’m naming these people in order to protect other actors from them. They’re monsters, they’re ogres. Chaplin was another one. Claire Bloom told me stories about how he terrified everyone on the set of LIMELIGHT.

Working with someone like Richardson you can ask, “Would you like working in CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE?” And the answer is, “It’s all right if you don’t mind getting killed on a horse.” Richardson let off firecrackers under the horses without telling the actors who were on them. So Alan Dowby, a friend of mine, ends up three miles away in another village on the back of a crazy horse. If that’s called artistic directing, then I don’t know.

DIRECTOR TONY RICHARDSON

EGAN—Is there the possibility that the director is aiming at something?

HOPKINS—Yes. Killing the actors.

EGAN—Look at Kazan. In ON THE WATERFRONT he would drink in a bar with the non professional actors to work them up for a scene and then get them on the set and shoot it.

HOPKINS—Yes. That’s what he does.

EGAN—Couldn’t Richardson and Preminger be doing the same thing but with a certain amount of brutality.

HOPKINS—I don’t know, but I know what I would do. I would chose not to work with the director. Look at Robert Mitchum. He walked off the set of Preminger’s ROSEBUD. Mitchum was right when he said, “Sorry, I’m off for home because I didn’t come into the business to get screamed at. If I wanted to be screamed at, I could have joined the marines.” I used to be scared of directors but I’m not anymore. I feel I’m beginning to know my job. If a director started screaming at me, I would walk off until the director calmed down, or I would walk away forever. I would risk that now. I wouldn’t have risked that a couple of years ago because I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll never work again.” But the truth is that if you work hard and an actor is good , he will always work.

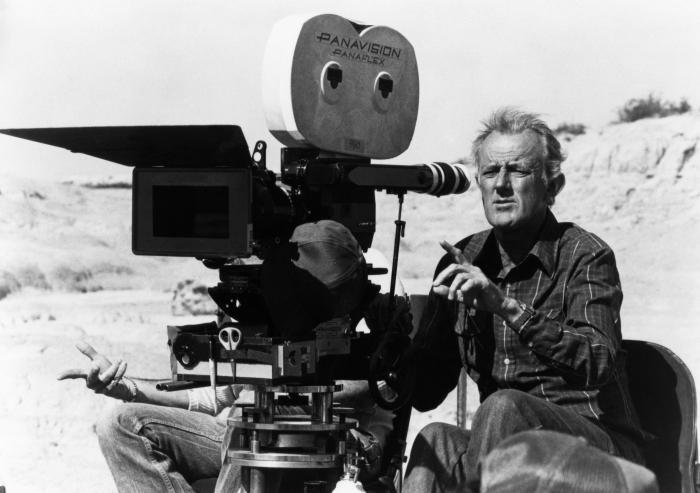

DIRECTOR OTTO PREMINGER

EGAN—You think that Preminger is scared of the actors?

HOPKINS—There is something. He’s got a monkey on his back. I met him in New York and he’s a very charming man. He’s a delightful man to talk to socially. But you get him on the set and he becomes Adolf Hitler.

EGAN—You really think he’s a sick don’t you?

HOPKINS—I don’t know. I know John Dextor is a sick man. A very sick man. I don’t hold him in any contempt or hatred. I feel rather sorry for him. The longer I’ve been away from him and the production I realize that I don’t owe him a living. He thinks, for example that Tony Hopkins owes him his talent. Well, that’s simply just not true. He says about himself, “If it wasn’t for me, dear, you wouldn’t be anywhere.” Well, that’s bullshit, too. That’s crap. Sure he gave me chances but finally, because I couldn’t stand bring screamed at, I walked away and stopped going to him for direction. And when actors do that to directors can they really be considered directors. It becomes a matter of luck for them.

EGAN—Walter Pidgeon worked with you in THE LINDBERG KIDNAPPING. He was at MGM for a long time. Did he ever speak about those days?

HOPKINS—He said it was wonderful there. They’d finish filming at the end of the day and they’d either go to Clark Gable’s dressing room or Spencer Tracy’s and they’d all drink. He said it was a like a country club.

EGAN—But if you read about someone like F. Scott Fitzgerald or Louise Brooks; people who had failed in Hollywood, they were treated like less than dirt. Even the place where you sat in the studio commissary was an indication of one’s importance at the studio, or lack of.

HOPKINS—It’s still like that in California, but it’s much more polite now. The knives are still drawn, but now it’s all run by executives behind desks.

EGAN—Truman Capote was quoted as saying that actors weren’t really intelligent. If they were, they’d realize how absurd it was to stand before a group of people and pretend they are something they’re not.

HOPKINS—Yes. We must be crazy to dress up in costumes and go on stage every night.

EGAN—There’s a story about Marilyn Monroe when she was at the actor’s studio. She become so immersed in an acting exercise that she became oblivious to everything else and without realizing it actually wet herself.

HOPKINS—Maybe the biggest mistake Monroe ever made was going with Strasberg and the actors studio.

EGAN—You really think so? Did you see BUS STOP?

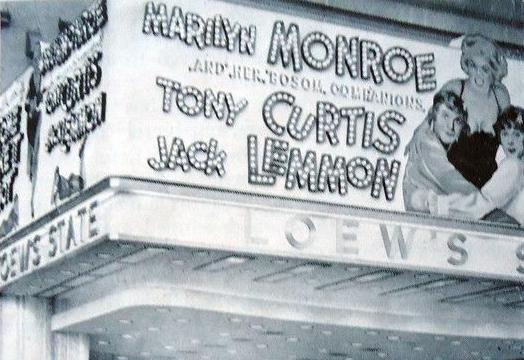

SOME LIKE IT HOT PLAYING AT NEW YORK’S LOEW’S STATE THEATER IN 1959

HOPKINS—She was terrific. But in SOME LIKE IT HOT, it was Jack Lemmon and Billy Wilder’s complaint that her lateness and forgetting lines forced them to do scenes over and over again. It drove them up the wall. Olivier went crazy when he directed her in THE PRINCE IN THE SHOWGIRL. She wouldn’t open her mouth unless she went and talked with Paula Strasberg for motivations and such.

EGAN—Poor Paula. Every director who worked with Monroe blamed her for everything. But you must admit that Monroe got better.

HOPKINS—She was a natural talent and got better, but she almost went crazy and committed suicide.

EGAN—I don’t think that had anything to do with her acting, but how she felt about her whole life

HOPKINS—Ok, maybe not.

EGAN—She did know the movie business. Wilder said about the extensive takes on SOME LIKE IT HOT, that when he came to cut the film, on all the early takes she was weak and Curtis and Lemon were strong. On the later takes she was strong and they were weak. Wilder was forced to use her best stuff and as a result Monroe always outshone everyone in scene after scene. She know exactly what she was doing. Look at THE MISFITS. She’s brilliant.

HOPKINS—She was terrific, but she killed Clark Gable. He was so bored with her coming late and all the waiting, that he did the stunts himself at age 59.

EGAN—Gable didn’t do the stunts because of Monroe. He wanted to do them. This was a very important film for him and he wanted to prove something to himself. His doing stunts gave his performance an enormous boost.

HOPKINS AND GOLDIE HAWN IN THE GIRL FROM PETROVKA

HOPKINS—What I’m speaking about is discipline. It always comes back to that. I don’t care how you get prepared, even if it’s standing on your head in the morning, as long as you’re prepared. The most pure thing that an actor can do is be prepared. Acting is basically a craft and an actor has to know his craft. Any actor who doesn’t, and gets paid an enormous amount of money like Goldie Hawn did when I was working with her on THE GIRL FROM PETROVKA, and who, like Miss Hawn, came to the set two hours late and doesn’t know her lines, shouldn’t have the job. If I had been the director I would have just said, “Screw it, off the set.” and gotten another actress. There’s no mystery to acting, and actors like Monroe or Hawn have brought an appalling reputation to the whole profession. I think it was Bogart who said, “The only thing you owe the public is a good performance.”

EGAN—Ultimately what is the satisfaction you get from acting?

HOPKINS—Basically each role makes one grow a little. Olivier said a marvelous thing about acting. He said that acting is the process of learning. It’s the sugar pills of knowledge. Instead of having to sit down with textbooks day in and day out learning English history, you can get it through Shakespeare. If you’re doing Richard III, for example, you read the footnotes and trace the history. Then, at the same time that you’re learning the history of the period, you are also beginning to learn the play and that’s very pleasant. In school I was bored by history. I hated it and couldn’t be bothered. I’m still lazy but when doing a part I must do my preparation by reading and studying the period. I didn’t know who the hell Hauptmann was before I did film. I had heard of Charles Lindberg and was dimly aware of the kidnapping. But when I started reading the script and then reading the research I thought, “My God, there’s so much more to learn.” It was a fascinating piece of social American History. Did you see THE ACCENT OF MAN.

EGAN—Sure.

HOPKINS—Although I wasn’t acting in it I did interview the scientists at the end of each episode and learned so much. I was always fascinated by science, but it is Bronovsky’s all-embracing vision; his Renaissance vision which I found so thrilling. What Olivier means. If you feed a little child medicine and give him a lot of candy to cover the bad taste, he’ll take the medicine and have a good time as well.

EGAN—And with QBVII, what about the research for that role?

HOPKINS— That obsessed me for months and months afterwards. I learned so much about concentration camps. I know exactly where the concentration camps were in Europe and found out exactly what was going on in each one of them. It made me aware that this can all happen again.

EGAN—Concentration camps were not barbaric. Barbarity is a knight with axe hacking heads off. The camps were a cold emotionless, efficient extermination machine. Order was the keynote. The victims walked quietly into the gas chambers. And isn’t order what civilization is all about.

HOPKINS—Yes. A legion of ghosts. It’s what Bronovsky said in THE ACCENT OF MAN. He said, “Truth or certainty about absolute knowledge and the danger of handling what one believes is absolute knowledge.” Hitler’s belief, his absolute knowledge of the superiority of the master race of the German people was ludicrous. He took millions of intelligent and very clever people by the nose and led them spellbound into hell. In the process, in Europe alone, he slaughtered thirty million people. For what? Absolute knowledge. No one possesses absolute knowledge. The marvelous and extraordinary thing in the tragic and comic history of mankind is whether man is created in a divine uncertainty or in a divine mistake. Someone said that God created the world in a fit of absent mindedness. Maybe he’s right. We are capable of the highest order of civilization and yet so capable of Auschwitz. We have a potential for evil which is matchless and a propensity for tremendous good. It’s a cross roads and the question is which one will we follow.

EGAN—The line between them is sometimes so thin.

HOPKINS—Let me tell you something. You just hit something that’s made me realize what we’re all capable of. For six months I’ve been planning a production of HAMLET. I wanted to direct the play and I was offered a chance to do it at the Westward Playhouse in California. So, a couple of weeks ago I started working on the whole thing. My vision of it was that I would be very generous to the actors and we would all have great fun. Then, as I was sitting down blocking the play, I was unconsciously playing the parts of not only Hamlet but also Gertrude, Ophelia and everyone. I was going to design it; costumes, music, lighting, everything. And if anyone got in my way I would have fired them all. Now that, in a mini way is what we’ve been talking about. So, I stopped and thought, “I’ve been screaming about directors, and yet I’m capable of such monstrous arrogance.” I thought, “This is a mistake” and for the time being put the project on the shelf. I’m going to wait until I feel I’m mature enough to do it; until I’ve sorted things out in myself first. Then, maybe, I’ll be ready and it will come to me.

EGAN—What is the next thing you’re going to be doing.

HOPKINS—BRIDGE TOO FAR; the filming of the Cornilous Ryan Book. I’m going to play Frost. He’s the Englishman who held the bridge.

EGAN—From what I hear it’s going to be the biggest film next year.

HOPKINS—I hope so. I’ve always wanted to get a good part in an important film. My agent seems to think it will do me a great deal of good and I think it will.

EGAN—You worked with the director, Richard Attenborough, before.

HOPKINS—Yes, In Young Winston. I played Lloyd George. It was a small part. Attenborough seems to be a director who knows exactly how he’s going to shoot something before he comes onto the set.

HOPKINS AS COLONEL FROST IN A BRIDGE TOO FAR

EGAN—How does it feel to be an actor on the rise?

HOPKINS—Lovely. Really, it feels nice. I’ve worked very hard and I’ve been very lucky. I’ve enjoyed my work and am still enjoying it. I’ve been going along on in an even keel; and building my career that way. I’m very glad it was nothing spectacular.

EGAN—Do you think that you now have more control over your career then you used to?

HOPKINS—Yes. Especially over the last year because I’ve gotten over the fear of being told what to do by rabid directors. I’ve finally walked away because I was becoming brainwashed by the fact that I thought I owed everything. I’m indebted to a lot of people who have helped me. People like Laurence Olivier. But you just can’t go on owning people. Eventually, you have to say this is what I’ve earned. This is mine.