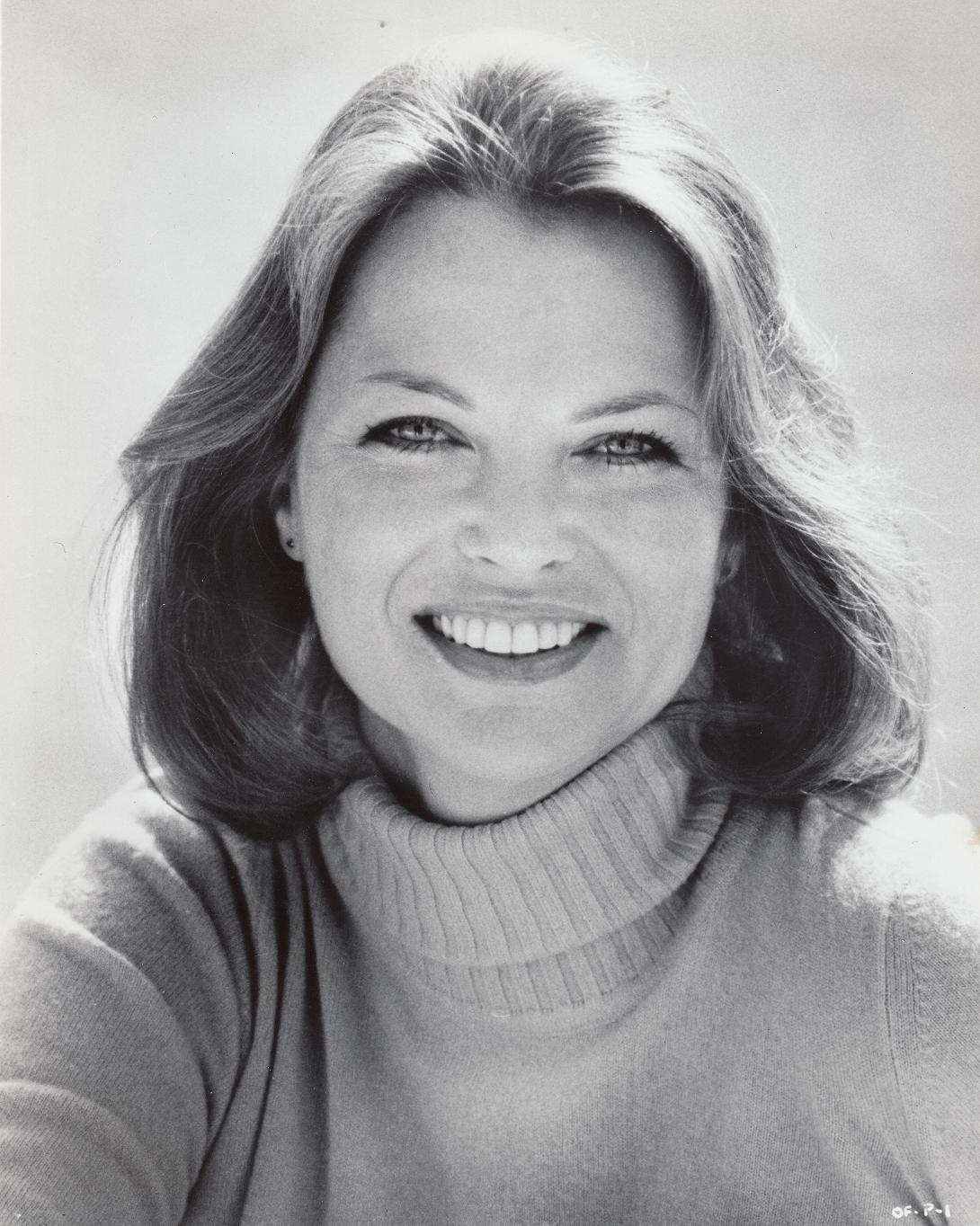

Louise Fletcher

In the fall of 1975 ONE FLEW OVER THE COOKOOS’S NEST had just opened in New York. At that time no one had heard of Louise Fletcher. I found the woman I spoke with on that November afternoon in 1975 an attractive forty year old who bared little resemblance to the character of Nurse Ratched, a role for which she would win an academy award and, years before, she would became Hollywood’s leading portrayer of harridans. In fact, the strongest memory I have of that day was of her searching through the hotel suite’s kitchenette looking for something for me drink. She found a warm bottle of coke in a cabinet and skillfully filled a class with ice and then poured in the foaming coke to the top of the glass without spilling a drop. Marveling at how well she did it, I thought as a struggling actress she must have worked as a waitress. When I commented on this asking her if she had been a waitress, Fletcher just shook her head and answered in a sweet little voice, “No. I’m just a mother.”

EGAN—When you got on the set in the morning for Cookoo’s Nest how did you get yourself ready, psychologically, to play something like Ratched.

FLETCHER—Well, in this film, the minute you walked into the door you were there. We filmed it in an actual mental hospital. Can you imagine going to work for twelve weeks behind bars. And then putting on those white stockings and those shoes that were like clunks, and putting your hair up into that vice, and that starched uniform, and a bra that was unbelievable. The minute I put on that outfit— and everybody is being so crazy and everybody else can just break out and be nuts and have fun all over the place—and I had to just sit there. That’s a crazy woman.

Fletcher As Nurse Nurse Ratched

EGAN—Then you believe Ratched was repressed?

FLETCHER—Totally. A virgin, or an aborted virgin. Maybe tried it once and was maybe penetrated a little.

EGAN—You know, you’re making me feel sorry for her.

FLETCHER—You don’t think there’s a redeeming thing about her?

EGAN—Oh, yes. There definitely is. You made her very human. But I’ve drawn the line. She didn’t belong in that hospital.

FLETCHER—You see, that’s the good thing about it. You can come out and have these mixed feelings about her. That’s what we all wanted. In the book she had rivets on the side of her body, and smoke coming out of her ears. She swelled up. You were seeing her through the eyes of a schizophrenic. How are you going to put that on the screen? It’s science fiction. That’s why these writers are such assholes for comparing the film to the book. We knew it would be different. We knew that the Kesey cultists would say, “Oh, my God, she’s not enormous and she’s doesn’t have big red lips and she doesn’t have big breasts.” We knew some people would be disappointed. But we set out to make a certain kind of move and stayed true to that ideal.

EGAN—You worked with Altman in THIEVES LIKE US. How would you compare working with Robert Altman to Milos Forman?

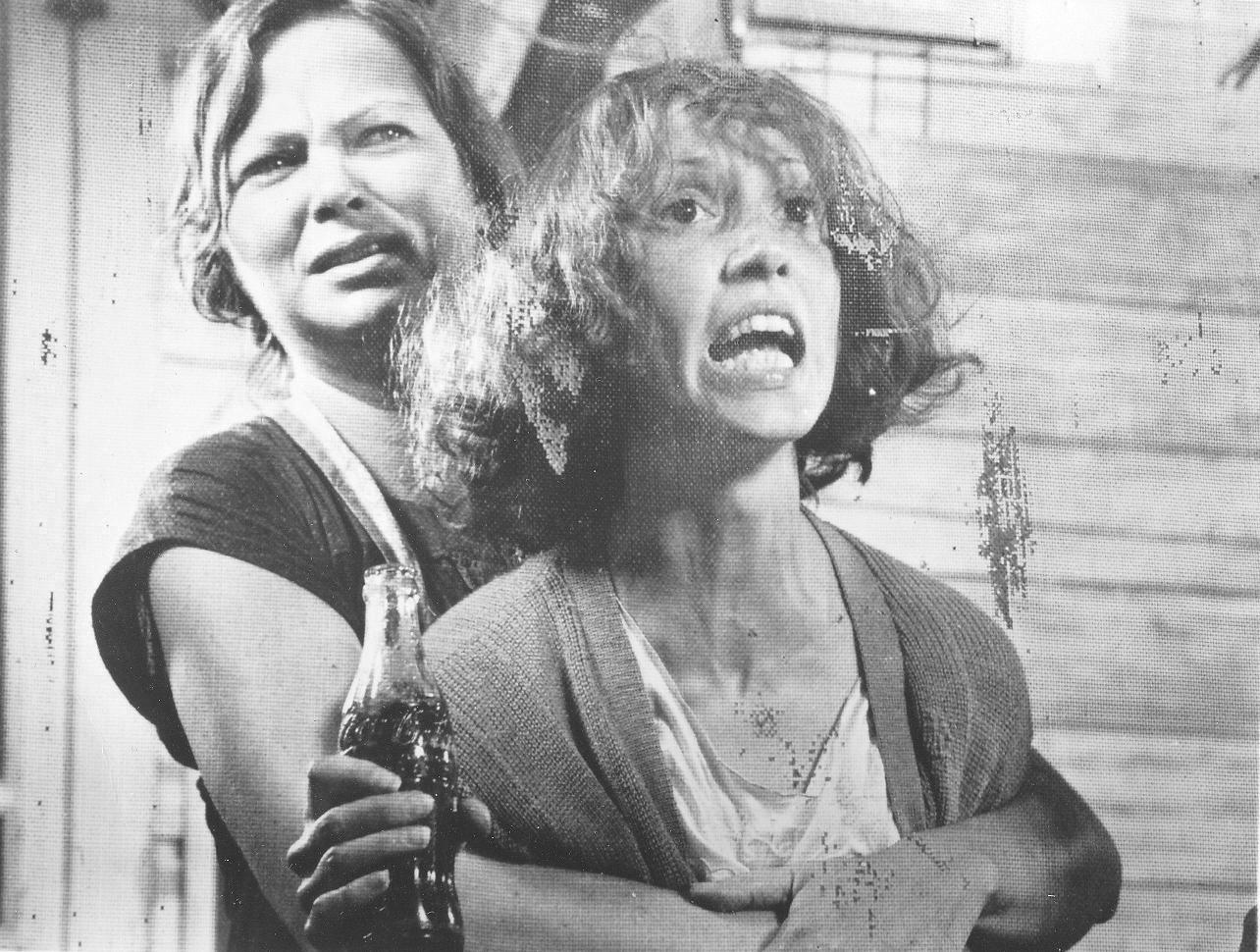

Fletcher And Shelly Duvall In Thieves Like Us

FLETCHER—Altman and Milos have something in common which is terrific. They love improvisation. They love to be surprised. They act as the viewer. They want natural behavior, but they don’t want to know about it. And they don’t want to talk about it. And they don’t want to explore it. And they don’t want to explain it. They both like actors to surprise them.

EGAN—Altman in particular; what does he do to get it out of you?

FLETCHER—He makes you believe that you are the only person who could possibly do this part. That’s what he does. He chooses you and you’re the only one.

EGAN—Almost like a daddy?

FLETCHER—On the set he is kind of a daddy.

EGAN—Do you perform like a little kid for…

FLETCHER—Perform for him? No. He trusts actors enormously; maybe even too much. I wrote a lot of dialogue myself in THIEVES LIKE Us. Sometimes he lets Actors run away with his film. He surprises you all the time. I’d go to work thinking that I was going to do one scene and I ended up doing something else. It sounds like I’m criticizing Altman and I don’t want to do that. I’m going through a tremendous feud with him right now and so I’m pretty touchy about him right now.

Lily Tomlin In Nashville

EGAN—Why?

FLETCHER—The part in Nashville that Lily Tomlin played. Well, I wrote that part and I was supposed to play it. Both my parents are deaf and I use sign language with them just like Tomlin’s character does with her kids. I spent a long time with Altman working on that part and then, when Altman went into production, he decides to cast Lily Tomlin. I’m very angry with him about that. It’s a wonderful part that was really mine.

EGAN—But you can talk about working with him. That’s not being negative.

FLETCHER—Well, Altman believes in the magic of acting. He believes that whatever happens because of this magic has to be right. So he lets it happen.

EGAN—As an actress, I would think you’d love him for that.

FLETCHER—I love and hate it. I think a director should have more control over what’s happening on a film. Altman would say that he’s only interested in telling the truth, and Milos would say the same thing. And the truth to them is what happens naturally. But Milos takes all this footage and then puts his mark on it. Altman more or less lets it sort of have a life of its own. Milos puts his stamp on the film in the cutting room. Altman puts his stamp on the film on the set. Also, another thing about Milos is that he begins shooting some scenes in close-up.

People want to know how does he get it to be so real. Most directors start when they’re far back in a master shot so they can do everything in long shot. They don’t miss anything. Then they move in for close-ups and you’ve done it and now it’s the second or third time. Forman wants the freshness to be on your face and in your eyes. He wants it to come across. He wants truth. So, you do an enormous scene, like a group therapy session, which runs for nine pages and he has the camera right in on your face all the time. The camera was so close that my hair was hanging on it. And whatever they say like “piss on your fucking rules Nurse Ratched,” it’s the first time you hear it and your reaction is there on your face.

EGAN—No rehearsals?

FLETCHER—No, because a lot of it is improvisation. The first time I’m hearing some of this, the camera’s in my face. For most of the scenes Milos had close-ups of everybody. Sometimes we had three cameras going at the same time. So it was all happening at the same moment. It wasn’t done a second time and then put together in the cutting room. Those reactions that you see are on the screen are the actual spontaneous reactions that the actors are experiencing.

EGAN—What do you think is the best reaction shot in the film.?

FLETCHER—It occurs the end when, after the Indian has gone out of the window, Christopher Lloyd sits up and sees him and begins to laugh. And then the laugh transforms into this weird face. It’s really brilliant.

EGAN—Why?

FLETCHER—Christopher’s character is the only patient in the group who has the same kind of energy that Jack Nicholson’s has. His character is angrier than Jack’s and he’s crazier than Jack’s, but he has this force like Jacks. So, Milos chose to end several scenes on Christopher.

EGAN—Why do you think Forman did this?

FLETCHER—He uses Christopher Lloyd as a dramatic punctuation mark in some of the critical scenes because Lloyd is crazy like McMurphy, rather than just crazy like the others and this tells us something about McMurphy.

EGAN—That he’s really crazy.

FLETCHER—Not only that but also how he’s crazy.

EGAN—You know, I didn’t think that COOKOOS NEST was as organic as other Forman’s I’ve seen like TAKING OFF or LOVES OF A BLOND. It seemed like pieces put together.

FLETCHER—I believe it’s the material. This is a story above all. It develops. He comes, he meets the guys, he has the confrontation with her, they fool around, they get naughty, they carry on, he learns about himself, he learns that he can’t leave. You have all these bits of information to get across and there are scenes after scenes after scenes. It’s the nature of the story. Didn’t you think the scenes with the doctor were brilliant.

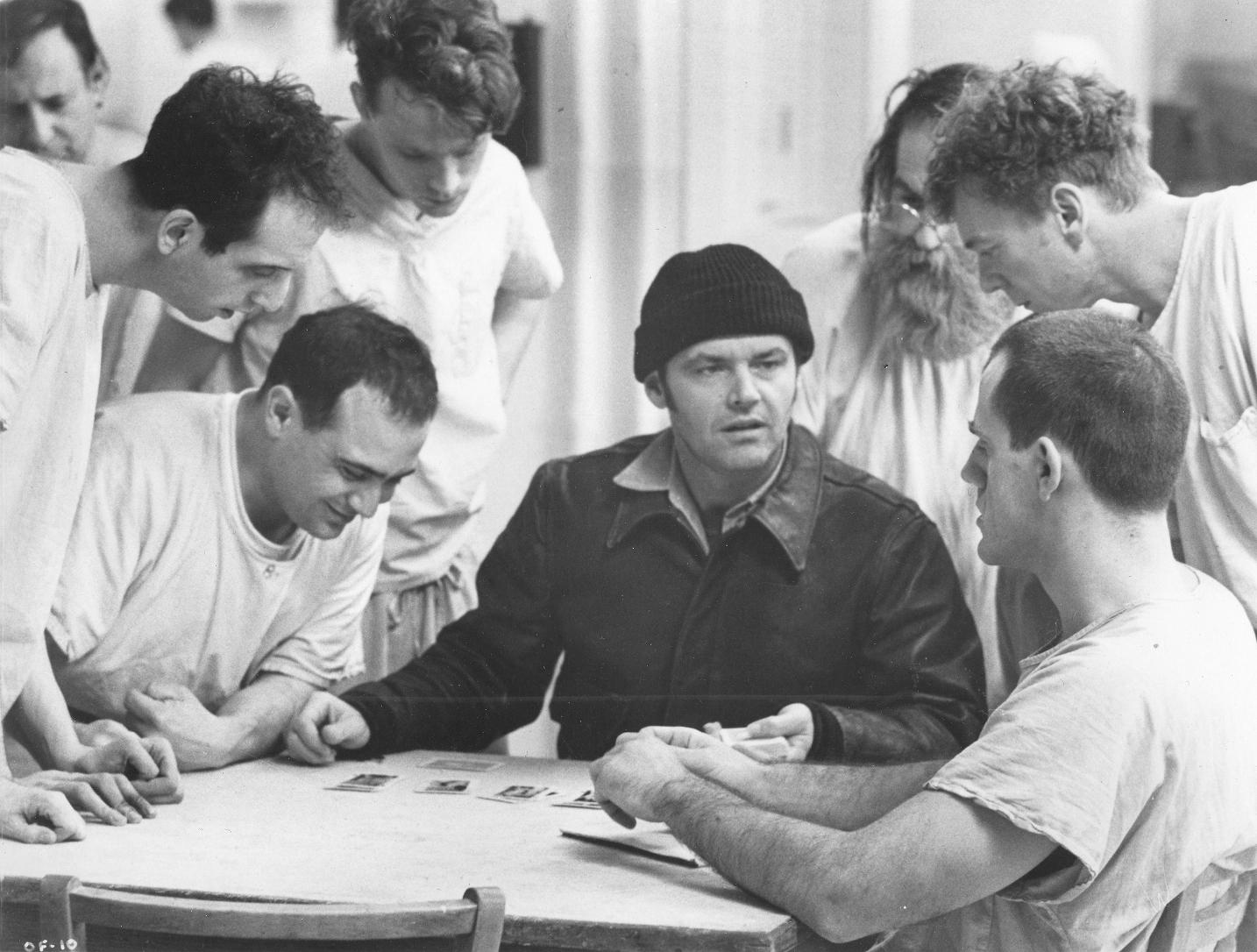

Jack Nicholson With Most Of The Cast Of One Flew Over The Cookoo’s Nest

EGAN—Fantastic. Intensely real but so subtle.

FLETCHER—Textbooks scenes. If the world came to an end today and we only had those two scenes, that’s what it’s all about. And that was a real doctor, you know, not an actor. That’s Jack Nicholson. Jack knows how to get that out of anybody. Of course, this is a real psychiatrist who does this day-in-and-day-out, so when Jack stamped out the imaginary fly, bug or whatever, Doctor Brooks went right along with that.

EGAN—Let’s talk about Jack Nicholson. Everyone must ask you about him. Are you tired of talking about him?

FLETCHER—No, not at all. He’s the best. He’s the greatest actor working in films today.

EGAN—How did you mesh with him?

FLETCHER—You can’t out do Jack Nicholson. I was faced with that the first day. I realized that there was no way that I could out shout him; out maneuver him; out physical him. So, what was left for me to do? Just lay back and hold all the aces.

Fletcher With Jack Nicholson

EGAN—I personally believe that your Ratched is the real force in the film. She’s a presence which is always felt. After all, we are in her hospital.

FLETCHER—I wish you were writing for The New York Times.

EGAN—Vincent Canby didn’t like you?

FLETCHER—His review was nice to me but he certainly wasn’t all that impressed.

EGAN—What I really liked about your performance was that it was so interior. From everything that I read about the film, I had expected a sort of Bette Davis performance.

FLETCHER—Everyone expects me to chew-up-scenery.

EGAN—It wasn’t that you played Ratched. You were Ratched. It was a performance that didn’t look like a performance.

FLETCHER-God, I’m glad you got it. When they had the screening in New York, Milos called me and he said, “Louise, I never thought that they’d get it. But they got it.”

EGAN—How could someone not get it.

FLETCHER—Time and Newsweek missed it. They just didn’t get it. But Pauline Kael got it. Rex Reed got it. Kael’s review is incredible.

EGAN—Which is interesting because everyone is saying that this is Nicholson’s best performance and I don’t really don’t think so. I prefer his work in MARVIN GARDENS.

Jack Nicholson In Marvin Gardens

FLETCHER—Really? That’s the weirdest thing I ever heard.

EGAN—Which do you think is his best?

FLETCHER—Maybe EASY RIDER. In that he didn’t seem to be acting. But I thought his performance in CHINATOWN was stupendous. It was so laid back. I didn’t feel it was acting there either. It wasn’t Jack doing his thing. He was really solid. He was really like Ratched in a way. At all times controlled. He didn’t do a lot o his Schick.

Jack Nicholson And Peter Fonda in Easy Rider

EGAN—I felt he did that here. But in CHINATOWN he was secondary to the camera. It was a Polanski film and Nicholson was a facet in the total.

FLETCHER—I understand that. That’s cool.

EGAN—Now, THE LAST DETAIL; in which he was brilliant, was a very theatrical film; an actors film and….

Nicholson In Chinatown

Nicholson In The Last Detail

FLETCHER—And COOKOOS NEST, isn’t it a theatrical film, also?

EGAN—Yes, but…

FLETCHER—You think it’s derivative of him?

EGAN—I think it’s a variation of what he did in THE LAST DETAIL. I think that he fell back on it. I don’t think that he was covering new ground.

FLETCHER—I don’t know how you missed it. You should have been there. Each day his face changed little by little. Till by the end I thought the man was going to really die. Really, he just died a little bit each day. His vulnerability. When he’s in that 2 ½ minute close-up at the end of the party, after he takes Billy into the room with the girl and he goes back and he’s listening to the train. The audience asks itself, “Is this guy crazy or not.” And then they think, “What is he?” It’s beautiful.

EGAN—I guess I missed it. Maybe I should see it again.

FLETCHER—Listen, Vincent Canby went back and saw it again. Charles Champlion went back to see it again. They both reviewed it twice. There’s too much that can be missed when you see it the first time. I know what I’m talking about. I was in the fucking thing, and the second time I saw it, I found myself saying, “Wow! Wow! Wow!” Take my word, there’s a lot in there.

EGAN—In that shot, I thought he was thinking, “Should I stay, or should I go.” I think he was really happy with those guys. They were his friends.

FLETCHER—Oh sure. I think he was thinking over the whole thing. He was thinking, “Jesus Christ, what am I doing.” And then he got a sort of insane look for a moment and he wondered, “I don’t know.” It was just a wonderful moment.

EGAN—Which brings me to you. In THIEVES and definitely COOKOOS’S NEST I felt I was watching a non actor. I didn’t sense a performance. It was totally internalized and so subtle. You only give hints of all that as happening inside. The expressions, the twitches on your face.

Fletcher As Nurse Ratched

FLETCHER—But you know, I didn’t know the twitches were there. We never saw dailies. We weren’t allowed to see them. Milos wouldn’t allow it. I was furious at the time, but he was absolutely right. I would have said, “Oh my God, my eye is sticking.” It was perfect but I didn’t know. It was that internal. That’s the way I work. I don’t know if I’m ever going to be able to do it again. In THIEVES LIKE US, I was familiar with that part of the country. I’m Southern. The minute I get off the plane in Mississippi or Alabama, I’ve had it. I’m back into the way I used to talk.

EGAN—Do you see each role individually?

FLETCHER—Absolutely. I have to approach each one individually and find the thing which applies to me. I can’t become. I have to find it to fit it into me. I can’t fit into it.

EGAN—I would think every actor has mechanisms and every role he goes to he applies them.

FLETCHER—Well, I can’t do that.

EGAN—It’s a kind of immersion, then?

FLETCHER—Yea.

EGAN—You really dig that?

FLETCHER—Yes I do.

EGAN—Why?

FLETCHER—It’s the most rewarding. I like to be real.

EGAN—Isn’t that kind of touching madness; to become, so totally someone else?

FLETCHER—Yes.

EGAN—Why then?

FLETCHER—Because it’s a joyful experience to watch the results. I love watching the results and saying, “Yea, I believe that,” or “I don’t believe that.” And, for the most part, what I did in COOKOO’S NEST is real. And that’s fantastic to me; that I could become that kind of person for however much time. The twelve weeks that we filmed I really got into it. We went out to dinner and I told everyone what to order. But obviously I have control over it. I don’t want to give the impression that because I thought Ratched was a virgin that I remained celebrate for twelve weeks. I’m not that deep into it. If I were, I would be worried about myself. It’s only during working hours.

EGAN—No. What, I’m getting at is this; what is madness? It’s going away, working out something and hopefully coming back. Is sort of what you do. Is it a kind of therapy?

FLETCHER—I love doing it. I don’t know how o explain it to you except that I love doing it. One of the reasons that I quit in 1962, and this is something that I haven’t really told anyone else, was because I was getting no joy out of it. The parts that I was doing were strictly sending telegrams. I could have dialed it in. My responsibility as an actress on a film is so different from my responsibility as an actress in a play that it turns me on more. Do you want me to explain the difference?

EGAN—Yes.

FLETCHER—My responsibility as an actress in a play is like this. You have a drawer and there’s something in the drawer. You’re on the stage and you go and open the drawer, but you’re not allowed to take the thing out of the drawer. Somehow you must register on your face, or in your body to the audience, the character of the thing that’s in the drawer. That to me is sending a telegram. It’s frightening; it’s funny; it’s whatever. As an actress in films that’s not my responsibility. It’s the director’s. If the director wants the audience to see what’s in the drawer, he’ll show it to you. I only have to react to it as a human being would. It’s real, its you.

EGAN—I always hear from actors how great the stage is.

FLETCHER—I like the stage. I’ve done it many times and I would like to do it again. But I would hope that I could incorporate some of what I have learned in films.

EGAN—Since by definition, art is really done for yourself, do you think that you can be more of an artist in film than on the stage. On stage it’s always to the audience rather than to yourself.

FLIETCHER—There’s always a risk in becoming vulnerable. You take a risk in life. You may get joy out of it, or you may get pain out of it. If you don’t take any risk, it’s zero. On film, if you’re right there and telling the truth, and you’re eyes have it, and you have it, and feel it, then you’re not lying to the camera. The camera believes you or it disbelieves you.

EGAN—Right, and then you do all this work and you have a shitty director and it’s all wasted.

FLETCHER—Ouch! I’ve been lucky so far. I’ve been very lucky. I’m really up against it now. I have to work again and I’m scared. I want to do something. How am I going to top this. How am I going to be able to have another, how can I say it, joyful experience as this one was?

Louise Fletcher In 2016